Iowa City - Dreamwell's theme for this season's shows is "Here I Stand," stories of people standing up against injustice or impossible odds. There could be few better shows, then, to begin this season than Arthur Miller's 20th-century masterpiece The Crucible.

Though Miller's text, like so many of his plays, is highly critical of American culture, John Proctor has earned a place in our nation's canon as an archetypal American hero. The protagonist's stark, sometimes foolish individualism speaks to ideals we hold dear, ideals that require incredible courage to fulfill.

The Crucible, under Scott Strode's direction, focuses on the struggle to be brave and speak the truth while the whole world is twisting and writhing with deceit, paranoia and hysteria.

The world of the play is absurd. The opening scenes are almost comic, with characters making ridiculous accusations of spectral murders. The Reverend Parris (Jim Evans), a petty, greedy creature, is portrayed with an excess of shallow showmanship. Ann & Thomas Putnam (Lois Crowley & Paul Freese) have been beset with misfortune and are looking for someone to blame. Parris' niece Abigail (K. Lindsay Eaves) and her friends are silly girls who want to cover up their minor misdeeds with wild stories. The new arrival Reverend Hale (Brett Myers) is a bright and eager young man schooled in the best Puritan learning and is only too ready to help these poor benighted folks find their demons.

All of this would be a perfect recipe for a farce were Miller not putting actual historical events on the stage. We know what happened at Salem, and we know how quickly a bit of silly superstition can spiral into mob violence. When Parris' slave Tituba (June Kungu) is interrogated about her "compact with the devil," she begins frantically to come up with a story that will save her from the rope. As she struggles to repeat the lines they are feeding her, it is so theatrical, so desperate and so obviously false that it is quite funny. It is possible to forgive Tituba, powerless and struggling for her life, for selling out her masters' enemies. When the children take Tituba's cue and join in, gleefully repeating the slander, the tragedy and absurdity rise to a fever pitch. The scene ends with Betty (Mira Bohannan Kumar) shouting names with the high-pitched energy of a young girl's game, spreading lies that will murder her neighbors as readily as children on the playground spread "cooties."

It is highly effective. Kungu, Myers and Evans are excellent performers, and the frenzy that builds in this first scene is both preposterous and yet completely

believable. The mob mentality is already out of control by the end of the scene, and the objections of the more sensible townsfolk are doomed from the beginning. John Proctor (Brad Quinn), Giles Corey (Scott Strode) and Rebecca Nurse (Bryson Dean) stand off to one side as this is going on, skeptical of the bright young scholar Hale, forming an tiny faction of dissent. They are quick to point out that people will say anything to keep from being executed, and that Putnam is looking to lay his hands on the lands of the accused.

believable. The mob mentality is already out of control by the end of the scene, and the objections of the more sensible townsfolk are doomed from the beginning. John Proctor (Brad Quinn), Giles Corey (Scott Strode) and Rebecca Nurse (Bryson Dean) stand off to one side as this is going on, skeptical of the bright young scholar Hale, forming an tiny faction of dissent. They are quick to point out that people will say anything to keep from being executed, and that Putnam is looking to lay his hands on the lands of the accused.Common sense and careful logic, however, have no place in the world of witch trials. The accusers are looking for invisible evidence, and the fact that they are looking for it is enough to let them see it everywhere. In such a world, a poorly kept pig becomes a cursed animal, a child's toy becomes a voodoo doll, and an off-hand comment about strange books becomes a death sentence. There is no way to disprove such allegations short of calling them nonsense, and to call them nonsense would be un-Christian.

The judge they bring in, Lt. Governor Danforth (Jason Tipsword), exemplifies this idea quite well. He will not hear the court's legitimacy questioned, and every attempt to bring the conversation back to the commonplace causes of the play's events becomes a dismissal of the importance of the spirit world. The debate becomes an exercise in circular reasoning: if so many people are in jail, there must be a fitting supernatural explanation. If the court has hanged twelve people already, how can it be considered valid if it pardons people now? Everyone should be happy to be brought in for questioning; why would they fear the court if they were not already in league with the Devil?

Tipsword resists the urge to exaggerate this part, and his performance is extremely effective. His Danforth is calm, cold, and infuriatingly rational. He is an expert lawyer, even if his logic is twisted and self-referential. He is a villain, but his humanity is what makes him effective. We see him sweat in the final scene, when dealing with the unpredictable and stubbornly moral John Proctor. He is a cold-blooded tyrant, but he is also a man with an agenda, and Tipsword's careful attention to the objective play and the twists and turns of the piece make a more believable, and therefore scarier, Danforth.

Tipsword scarcely swaggers or rails; indeed, Evans' hot-headed Parris seems cartoonish compared to this careful, professional, but altogether ruthless representative of the State. At the same time, he seems completely aware of what is going on. He is careful around Abigail not because he is fooled by her but because he needs her. If the Salem Witch Trials are a piece of deadly theatre, Danforth is the director and Abigail the star performer.

K. Lindsay Eaves' Abigail Williams is the polar opposite of Tipsword's Danforth. She is loud, she is lusty, she is ridiculous, and she is very, very dangerous. It is clear from the very beginning that Abigail is in charge of the clique of Salem girls. Her silent scene work and the work of her partners (especially Kelly Garrett as Mary), shows the relationships very quickly and effectively. Eaves does not have much dialogue in the first scene, but she is a very powerful presence on stage, listening and watching, planning and conniving.

By the end of the play, with the help of her chorus of hysterical playmates, she has the entire town in the palm of her hand. Every time someone tries to get to the heart of the matter, Abigail is suddenly beset by invisible demons, and it is impossible to talk about anything so boring as disputes over lumber, cows, or golden candlesticks. Proctor thinks he can end the madness and save his wife by admitting he slept with Abigail, revealing the entire plot as a mad child's jealous vengeance. In doing so, however, he underestimates Abigail's skill at theatrical distraction. It is in this context that The Crucible is so effective for a modern audience; the play was written nearly sixty years ago, but the "look at me!" tactic Abigail employs in every scene is all too familiar from our contemporary political culture.

Because of this, the play is difficult to watch. It is infuriating at times, because it is an extremely effective indictment of the irrational behavior of crowds, of greedy, petty hysteria, and of cold-blooded hypocrisy. It seems that, in Strode's Crucible, absolutely everyone is in on the joke. Every single character knows the witch trials are a sham, but very few are able to admit it. Abigail needs the pretense to protect her reputation. Putnam needs the pretense to expand his territory. Parris needs the pretense to control his congregation, just as Danforth needs it to maintain his authority over the state. What is clear from the direction and the acting is that everyone knows it is a lie. The dramatic question, then, is whether anyone has the courage to tell the truth.

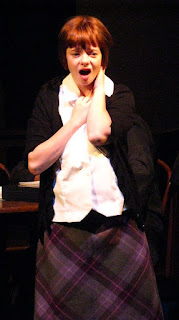

Mary is the first one tested, and in a tear-jerking scene, she comes before the intimidating Danforth, charged by John Proctor to reveal her part in the plot and save his wife Elizabeth (Traci Gardner). Garrett is incredible in this scene as Mary

struggles desperately to resist the badgering of Danforth and the murderous glare of Abigail. The scene is an incredibly energetic roller-coaster, and Garrett never checks out; she is completely engaged as everyone on stage tries to play out their agendas through her. A particularly beautiful and pitiful moment is when she silently begs the ruthless Abigail for mercy. When she finally caves and loses her courage it is devastating, and though we despise Mary for her cowardice, it is impossible not to have sympathy with her as we witness the intensity with which the other girls bully her into submission.

struggles desperately to resist the badgering of Danforth and the murderous glare of Abigail. The scene is an incredibly energetic roller-coaster, and Garrett never checks out; she is completely engaged as everyone on stage tries to play out their agendas through her. A particularly beautiful and pitiful moment is when she silently begs the ruthless Abigail for mercy. When she finally caves and loses her courage it is devastating, and though we despise Mary for her cowardice, it is impossible not to have sympathy with her as we witness the intensity with which the other girls bully her into submission.Mary Warren did not hang at Salem; she chose to redact her statement when her friends turned on her, and save herself by accusing her master. Spurred on only by Proctor's encouragement, from Gospel, "Do that which is good, and no harm shall come to thee," she cannot follow through. For Proctor is wrong; doing that which is good will cost Giles Corey and Rebecca Nurse their lives. It will cost him his. Mary is too weak to tell the truth if it means her death, so she gives in and runs back into the arms of the Salem coven, shifting the attention to our play's protagonist.

It is this that causes Hale to dramatically denounce the court. Historically, Hale probably did not turn until later, when his own family was touched by the hysteria. Miller, however, uses Hale as an effective moral tool, arguing for Christian charity and reason directly to the face of the symbol of tyranny, Lt. Governor Danforth. When he is not swayed even though his "justice" is depopulating the town, Hale attempts to convince Elizabeth to save her husband. "Beware, Goody Proctor," he counsels, "cleave to no faith when faith brings blood." Aloof from the dreary Puritan faith of Danfort and Parris and the reckless heroism of Proctor, he pleads for reason, compassion, and life above all else. He is the bright light of hope in this play, and Myers is excellent in his portrayal. He is charming and infectious, though a bit foolish, in the first act and admirable when he chooses to do the right thing in the second. Myers is a very generous scene partner, and he is a joy to watch with Quinn, with Tipsword and with Gardner.

Proctor, however, cannot finally stomach Hale's counsel. His fiery speeches, delivered here with tireless energy by Quinn, are why we come to see The Crucible. Even after he attempts to reach a reasonable agreement with an unreasonable court, and tell a ridiculous lie to gain his life, they are not done with him. They want him to act as a witness to help murder his friends' wives. In the end he stands up for himself, shouts down Danforth, and accepts his fate.

Miller could not stomach the Mary Warrens of the world, but said during the Red Scare of the 1950s that he "had as much pity as anger toward them." He refused, however, to name names in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee himself, and he will not let Proctor do so either. Proctor would rather die than be used as a tool, and even if it is hopeless he will not live on the blood of his friends. Quinn's tireless commitment to these later scenes makes this play a startling reminder of the courage of the human spirit, and serves as an inspiration to face down all the smaller injustices we see in our daily lives.

Strode's direction highlights the most valuable theme of The Crucible - the difficulty and necessity of resisting social pressures and speaking from the heart. There is a clear understanding of the dramatic throughline, and the entire production is engaging and effective. The stage is used quite well, employing a thrust to bring the intense court scenes right up to the audience. The actors have done their homework and work through the story with confidence and commitment. The lighting and costumes (Brandon Tanner, Rachael Lindhart) flesh out the story quite well, creating just the right tense atmosphere for the dangerous and irrational world in which the actors play.

I highly recommend you see The Crucible; it's a very powerful story executed with care and skill. It runs until October 8th at the Universality Unitarian Society. Bring some tissues.

1 comment:

Great review! I'm flying in from New York just to see this!

Post a Comment