Iowa City - Seating myself in the Unitarian Universalist Society of Iowa City for Dreamwell's "Writers' Skirmish," I found myself captivated by ambiance and watercolor paintings, abstract suggested explosions of plant pollination, red dandelion heads, the dispersed fire over a chalice. The woody old floors, the fold-out chairs, the wheelchair lift beside the slightly upraised stage, everything illuminated by big moon-like lights and a dim fluorescent indigo from behind the white backdrop of the stage. The place was very warm but so was the hospitality, welcoming the audience this summer Saturday night to celebrate strong character through a series of three one-act plays, winners of the Skirmish's theme "Here I Stand."

The first play presented was James Grob's Some Assembly Required, directed by Meg Dobbs.

(Pictured, L-R: Melinda Kay as Carolyn, Linda Merritt as Gina, Monty Hendricks as Josh, and Traci Schoenle as Linda in Some Assembly Required by James Grob)

(Pictured, L-R: Melinda Kay as Carolyn, Linda Merritt as Gina, Monty Hendricks as Josh, and Traci Schoenle as Linda in Some Assembly Required by James Grob)The sign is pivotal in the simple plot: The woman, named Gina and played by Linda Merritt, planted herself in front of a courthouse holding the aforementioned sign, and was investigated and examined by a series of allegorical characters who, in the process, did their best to define freedom before the cops break up the party at the request of local businessmen unhappy with the disruption.

The events and message are clearly opinionated, but raise interesting questions about how the overuse of a word or symbol can confound its meaning to the individual, and illuminating the ways in which people can be pitted against each other by real or prescribed roles, though they may actually be in agreement.

The dialogue overall was a strength in the show, witty but natural, delivered nicely by the talented cast. The banter between the characters Gina and Carolyn the reporter, played by Melinda Kay, was especially enjoyable and drew real laughter from the audience. The performances were further enhanced by costume that communicated perfectly who these people were before they even spoke: disgruntled housewife, young reporter, wet-eared cop, overgrown trust fund kid, patriotic soldier. They served well enough as embodiments of different types of American people and attitudes, yet lacked the diversity of representation required for their intended purpose. Nevertheless, they were a strong cast of characters and actors.

I was impressed with the final scene. It was well-executed, drawing the audience in through lighting, sound, and the centering of the action outside of the stage, in front of the characters as they looked out upon us. It was, in a way, unsatisfying, and very relevant to current events.

The set for Carrie and Richard New's Afterwerx, directed by Brian Tanner was also initially simple, gaining complexity through effects and direction; it consisted of a dark blue sofa, a stool, a four-legged teal table with a laptop atop it, and a grey folding chair. This made up the waiting room for the Afterwerx office, a company which sends individuals into the afterlife to track down and make amends with the dead (for a steep fee) in order to assist them in overcoming the regrets of their lives. Quite another dimension to the show was added when, as the characters descended to the afterlife, they also descended from the raised stage to the open space directly before the audience, heavy wooden doors closing behind them, light changing, and a large pillar introduced declaring whether they were at level one, two, or three of the underworld.

Particularly adding to the ambiance of this work was the lighting, which flashed at the appropriate times signalling the imperative to descend another level, brightened and lowered between scenes and at one point impressively highlighted the setting when dimmed in synchronization with the entrance of the slow, dark shambling of several extras posing as the dead. I would have been delighted with the skilled scene-setting, if not for the chills up my spine. The three-dimensional atmosphere was also enhanced by the actors coming and going from the stage through the seating area of the audience (a method which was also used in Some Assembly Required as Steven the police officer, played by Nate Sullivan, made his entrance and exit).

The acting in Afterwerx left something to be desired, with a few flubs and performances tending more towards wooden than engaging. It is unfortunate that a mistake in line delivery seemed to throw off the mood of the scene, which could have been recovered more gracefully through a little impromptu ad lib to maintain the realism of the dialogue. However, Brad Quinn's portrayal of Grey, nervous and slightly ticcy but well-meaning, was endearing and stood out in this play in terms of acting.

(Pictured, L-R: Melinda Kay as Melanie and Brad Quinn as Grey in AfterWerx by Carrie and Richard New)

(Pictured, L-R: Melinda Kay as Melanie and Brad Quinn as Grey in AfterWerx by Carrie and Richard New)The script was phenomenal, the mystery of the motivation for descent and the secrets within keeping me enthralled, as evidenced in my notes which were repeatedly interspersed with "What's going on?"

The ending was a mild twist-- not shocking but unexpected enough and foreshadowed very well. Bravo to the suspense of the script which, along with the immersive nature of the production, made this an engaging experience.

The final play in the sequence -- and the winner of the Skirmish -- was Amy White's World's Teeniest, directed by Matthew Falduto, taking place in a cluttered apartment setting where a woman played by Noel Van Den Bosch attempted to unpack in while trying to remain undistracted by an intruding little girl. The girl, played by the wonderfully talented Mary Vander Weg, seemed an unwelcome visitor, digging through boxes, asking questions, forcing answers. The woman was unreasonably short and harsh with her, for reasons becoming clear as the script and allegory elegantly unfolded.

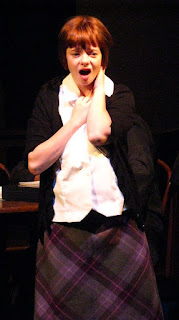

(Pictured, L-R: Mary Vander Weg as Girl and Noel Van Den Bosch as Woman inWorld's Teeniest by Amy White.)

(Pictured, L-R: Mary Vander Weg as Girl and Noel Van Den Bosch as Woman inWorld's Teeniest by Amy White.)The pacing of the piece is exceptional, and I enjoyed that the exact allegory was never completely revealed but had to be deduced by the audience. The elements of the metaphor are very specific and it is clear, as Falduto stated in his notes, that every line and action is imbued with the message of the play. However, this was also a drawback.

Once the puzzle began to unravel, a strong political message revealed itself. Although it was a skillful and creatively designed argument, the message it carried was more pushy than persuasive, giving too many firm answers and asking too few questions, heavy-handed enough not to ruin but certainly to distract from the superb acting, dialogue, and direction. Despite this and the weightiness of the issue, the play remained for the most part light-hearted, centered and drawing on the energy of Vander Weg's character.

As in the first play, the ending is aesthetically pleasing but not what you would call a resolution. It is interesting to note that these demonstrations of powerful stands against opposing forces were not necessarily happy or "all loose ends tied" types of finales. That, along with the effects and immersive direction of the plays, delivered a solid experience that I would recommend. It was refreshing to see these fictions reveal such a relevant truth: that although taking a stand for what one knows is right is, well, right, the end results can be bittersweet. An important lesson to remember, delivered by a talented ensemble of original minds.

"Writer's Skirmish" plays again July 20 and 21 at 7:30 at 10 S Gilbert St. in Iowa City. Tickets are $13 ($10 students & seniors).